Last week I finished watching the second season of the television show Landman.

The mechanics of the oil industry — explorers, prospectors, and the oil crew — were superbly explained. My only complaint was that we did not get more details on the boring stuff, and instead got a lot of emotional drama between the ridiculously attractive cast, but I digress.

It is rare to watch some mindless TV at the end of a long day and walk away with an interesting hypothesis about how to live life, and build for success but one of the advantages of fiction is that it strips away the polite abstractions that constrict our lived reality and shows us how things could, or do, actually work. And once that was stripped away, I had some deep thoughts.

The protagonists in the show eventually find their way to success because they take enormous risks and, crucially, are able to find funders willing to bear those risks with them.

BUT, heroic as they seem, if you look closely, you will see that they are not taking on unimaginable, unbounded risks or acting wildly irrationally (at least not by 2025 standards). They are operating inside a rules-based system that has already done much of the work of absorbing failure at a certain price point.

I mean, the risk is insured, the capital is pooled, and the downside is capped - and so what looks like courage is actually a lot of maths performed by ‘grasping’ institutions that know how to price loss and have balance sheets large enough to make a hundred such bets.

It follows, then, that one of the biggest differences between rich and poor groups of people, as they exist today, is not how ambitious people are or how their culture primes them for pushing ahead, but how expensive, embarrassing, or financially detrimental it is for them to be wrong. Here I’m assuming of course that risk-taking is a proxy for wealth - perhaps it is in the collective, not always so in the singular.

In places where failure is “not good” — leading to permanent debt or the loss of a good life — people behave cautiously, not because they lack ideas, but because the expected value of experimentation is negative. The safest strategy in such systems would be to avoid variance altogether, and stick to non-risky paths.

And so back to Landman, I left the season finale feeling that the number of shots you can take… is such a good proxy for your group’s or your country’s development. When most people are willing to try new things, to start companies, or to invest in uncertain outcomes, it usually means the system has learned how to catch them when they fall, rather than pushing them to the back of the line. When they are not, it often means the opposite: that the system is perfectly capable of letting people fail, but not very good at helping them recover.

You could pick something out of a newspaper, and say “hey, look, he made it”, but per capita GDP probably tells a better, more consistent story. One rags-to-riches success does not make a first world country.

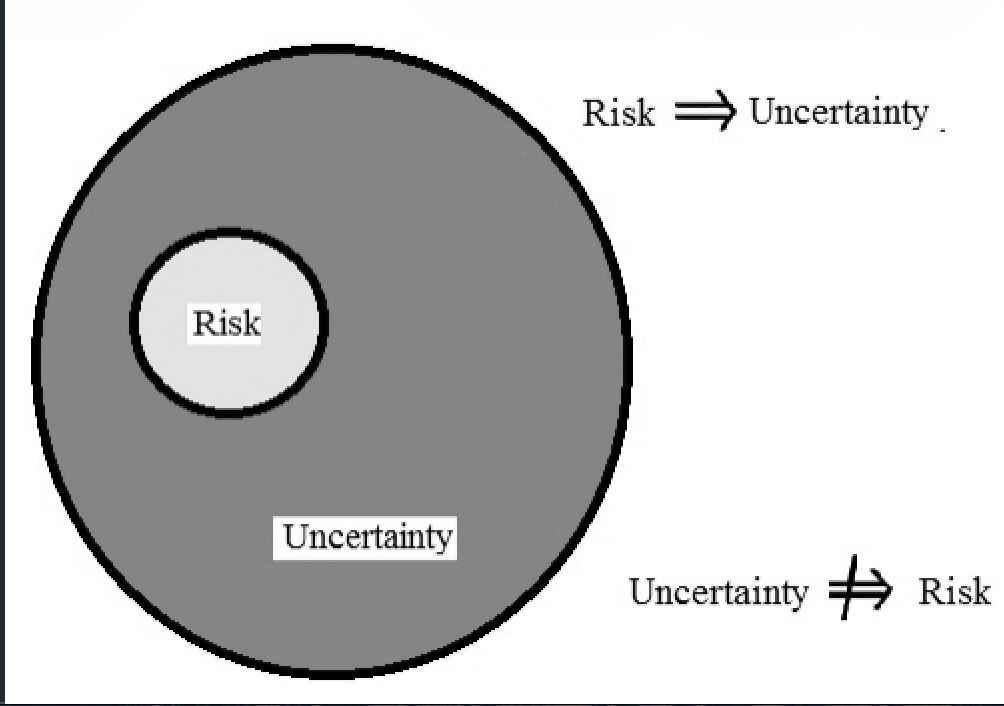

To this end, many countries have standardised the absorption of risk - through welfare, strict liability laws, and well developed insurance markets. From this perspective, as an individual who wants to take more shots at risky ventures, the right move is to shift your loss-taking capacity to someone else. When failure is priced, experimentation becomes ordinary. And when experimentation becomes ordinary, progress tends to follow without anyone having to talk very much about progress at all. Which brings us to the idea of uncertainty. As I kept thinking about the season finale, I did some reading around the distinction between risk and uncertainty, which are often used interchangeably but are emotionally and institutionally very different.

Risk is something we are generally willing to tolerate because it can be measured, priced, insured, and shared - as we discussed above, but uncertainty, by contrast, is open-ended, and a blackhole where outcomes are unclear and the downside is impossible to fully understand.

What could hold most people back when they have risk-taking capability could also be the far deeper discomfort of stepping into uncertainty, where there is no clear framework for anhything. Perhaps - and I could be widly wrong here, developed systems work largely by converting uncertainty into risk — by engaging in multiple such activities and taking those results as boundaries for how to think about risk.

As a parent? My takeaway is to make it easy to bounce back after failing, and make it fun (and important) to try. The hard part, once you buy into this line of thinking, is probably the emotional cost of failure. Another useful skill to teach our children may be the ability to not fear the unknown - a weighty, and worthy task.